Juneteenth: Origins and Myths

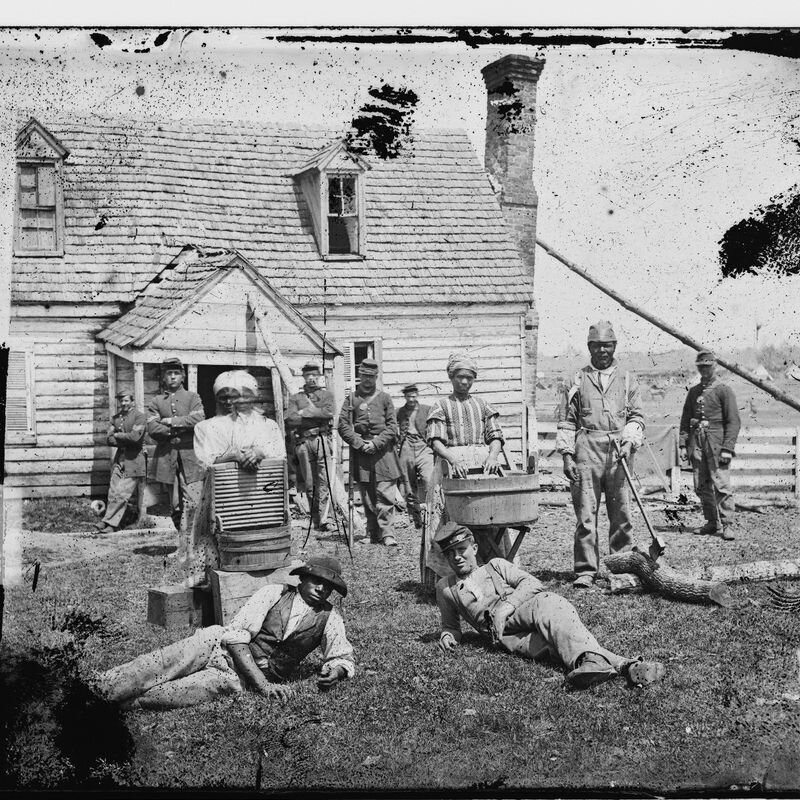

Fort Monroe, Hampton, VA. The site of the beginning of the end of slavery,” as Harvard historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. once said. (Photo: US Library of Congress)

The Juneteenth story starts in Galveston, Texas. In the early 19th century — the middle period of the Transatlantic slave trade, this coastal Texas town, just 800 miles from Cuba, was an integral global trading hub, and a go-between for colonists, traders and enslaved Africans from Cuba.

In this period, the Yoruba came to Texas in significant numbers, trans-shipped from Cuba where they were brought from West Africa to work on sugar (and coffee) plantations. By the 1850’s Cuba was the sole importer of enslaved Africans in the Americas. In the U.S., the institution persisted, but the direct importation of captive labor to the United States directly from Africa did not.

Given the cheap and abundant labor in Cuba, and its close proximity to the United States, it was a hub for human trafficking. Colonists could easily sail to Cuba and buy Africans for $300 or $400, return to Texas, and sell them for as much as $1,500. These high profits, and Texas’ non-compliant, border state status, brought an influx of enslavers to Texas, where slavery was technically illegal, but functionally very active.

Black families in Galveston and Houston were particularly isolated. So isolated in fact, that even though the Emancipation Proclamation was issued Sep 22, 1862, and went into law January 1, 1863, it took more than two-and-a-half years for the news to arrive to the state of Texas.

The emotional spirit of Juneteenth is one of celebration, but the origins of the day, rooted in the Emancipation Proclamation, are judicial. In the widely circulated story of General Gordon Granger’s decree from the balcony of Ashton Villa, on June 19, 1865, ( “All persons held as slaves within any States…in rebellion against the United States, “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”) it should be noted that it was not the decree that delivered the freedom, rather a position of political strength that afforded enforcement of policy and ultimately, the actualization of emancipation.

The upholding of laws were made possible by the Union victory. The Union victory was made possible by hundreds of thousands of Black men and women whose arms and labor begat their own freedom. Notably, in the famous Proclamation, more words were dedicated to the exceptions of places where slavery could endure, than the announcement of liberation itself.

….the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth[)], and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

In 1861 and 1862 the U.S. Congress passed successive versions of the Confiscation Act, a law that seized weapons and property from enslavers refusing to free enslaved laborers. Many of those released would go on to take up arms in the war against the South, and many others did not wait, or were not granted this release, and freed themselves. These were the freedmen, the 200,000 Black soldiers who took part in 200 battles, and the 300,000 more who were effective laborers. Without them, the Union could not have defeated the Confederacy, as Lincoln himself said, “Without the freedman, the war of the Union could not have been won.”

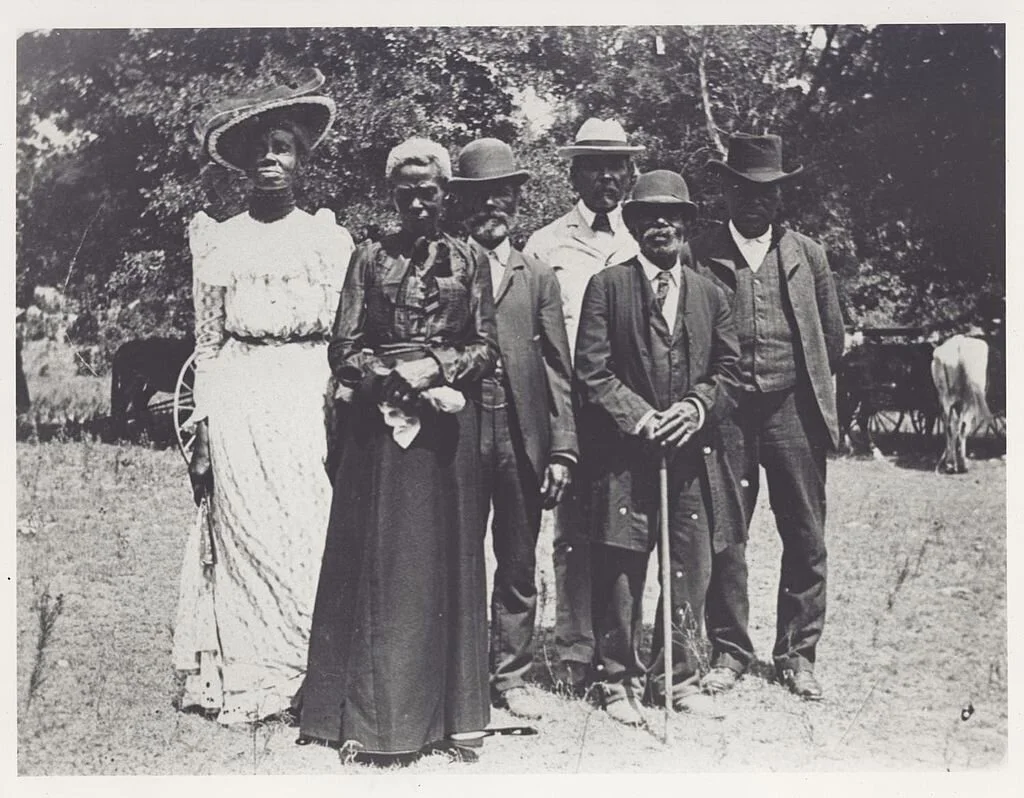

An early celebration of Emancipation Day (Juneteenth) in 1900. The Portal to Texas History Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Here’s the thing to take away. As always, marginalized people, in this case, Black people, are instrumental in their own liberation! Stories that fixate on the policies and politicians, rather than the groups who liberate themselves, further “white savior” colonial mythology. What did the Black folks do once they once they got free? Bought land, of course. And they celebrated with fishing, barbecue, rodeos and baseball games.

Professor of history and foodways Fred Opie writes that some historians believe the red color could be connected to “the Asante and Yoruba’s special occasions which included offering the blood of animals (especially the red blood of white birds and white goats) to their ancestors and gods.” So on Juneteenth, our food is red! You can read our friend Nicole Taylor on this topic, and here too.

- Stephen Satterfield

Citations

The Origin and Development of the African Slave Trade