It’s Time to Decolonize Tea

By Charlene Wang de Chen

A tea worker carries her tea-picking ladder in Phoenix Mountain, Guangdong. Photo by Charlene Wang de Chen, Tranquil Tuesdays.

One of the most worldly and globally sophisticated people I know introduced me to his prized collection of Mariage Frères teas. They were French. From Paris.

French tea? They don’t grow tea in France. This “French” tea was Chinese, Indian, Sri Lankan and Japanese tea repackaged in French branding.

At that time my friend and I were both living and working in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Bangladesh is a tea-producing country.

Something similar happened again a few years later.

While living in Beijing, I visited a friend’s organic farm on the outskirts of the city. The founder, a fellow American, brought out a special tin of tea to share with the group: It was Mariage Frères tea. Again, France does not grow tea, it only has a colonial trading relationship to tea. We were in China—the world’s largest and oldest producer of tea.

Fuding Tea Growing Region in Fujian, China, one of the country’s 18 provinces that grow tea. Photo by Charlene Wang de Chen, Tranquil Tuesdays.

The fact that both encounters with this “French” tea were examples of people going to great lengths to bring tea that had been exported from Asia to France, back into two historical tea producing countries, highlighted the absurdity of what colonial mentalities can create.

Ever since these two encounters, I have sought to learn as much as I could about tea, and specifically Chinese tea. For seven years, I lived in China to start and run a tea social enterprise, learning from local tea experts and working directly with small family tea growers to showcase the richness of China’s teas and tea traditions to new audiences.

My experience navigating the global tea market and talking to many tea drinkers from around the world made me realize that in the 21st century, we have yet to decolonize tea.

It is time for us to decolonize tea. What I mean by “decolonize tea” is, it is time for us to learn and recognize the actual historical colonial systems of the global tea trade. It also means it is time to confront our inherited colonial mentalities that European tea processes and culture are superior. And lastly it means restoring an appreciation for tea as a seasonal crop grown and crafted by people and discard the colonial idea of flattening tea into a commodity.

In the words of George van Driem in the Tale of Tea, “Ever since tea had been transformed from a medicinal condiment into a beverage, tea has always had everything to do with taxes, money and politics.” He traced the timeline of tea’s entanglement in taxes, money, and politics back to eighth-century China.

Ancient wild tea trees grow in Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, the region recognized as the birthplace of the tea plant, camellia sinensis. Photo by Charlene Wang de Chen, Tranquil Tuesdays.

The tea plant, camellia sinensis, is indigenous to the area of Asia that overlaps present day China, Myanmar, Thailand and India. Tea cultivation and tea consumption in present day China are found in records from the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE). The first written records of a European encounter with tea are from a Portuguese traveler in Japan in the 16th century. It isn’t until the 17th century, however, that the global trade in tea starts shifting from a Chinese- to a European- and then British-dominated global trade.

In the intervening 900, almost 1000 years between the eighth century and the 17th century, elaborate and everyday tea culture, industries of cultivation and traditions flourished in China, Japan and Korea and their trading partners. For instance starting in the eighth century China traded tea with Tibet for horses to increase Chinese military capacity. At the same time a whole literary and aesthetic culture to celebrate tea drinking developed in China. Asia and the Near Eastern world had their own thing going on, enjoying and trading tea before the Europeans decided to show up and crash the party with colonialism.

From left to right: Painting by Qian Xuan (1235-1305) of Tang Dynasty poet Lu Tong, famous for his poem “Seven Bowls of Tea”; 6. Painting by Wen Zhengming (1470-1559) of tea gentlemen aficionados drinking and brewing tea; and 7. Painting by Tang Yin, Ming Dynasty era (1368-1644) of gentlemen engaged in a leisurely tea brewing competition. All images from the collection of National Palace Museum in Taiwan.

Drinking a cup of tea grown in Asia or East Africa, somewhere in North America or Europe is sipping a tangible vestige of colonial empires and trade routes. The Dutch East India Company brought the first tea to Europe from Japan and China in 1610. The British East India Company, legendary instrument of British colonialism, officially entered the tea business in the 1660s. Not only were these companies responding to the newly acquired desires for this Asian luxury beverage, but the tea trade was an integral part of the transatlantic trades for sugar, enslaved people, cotton, silver and later illicit opium. These enterprises fueled European industrial capitalist development and enrichment. In 1836, the taxes traders and consumers paid on Chinese tea were enough to cover over 112 percent of the British Royal Navy’s annual expenditure.

Profiting from the taxes of trading tea wasn’t sufficient. Europeans went from being importers with no direct control over production in spices, coffee and tea to gradually becoming directly involved with growing the crops, manufacture and sales.

Among the items most desired in the European colonial market, tea was unique because the Chinese government prevented European attempts to take tea plants, tea seeds or the knowledge required to grow and make tea. The entitled desire for more access to more tea led to two Opium Wars—both of which had more to do with tea than opium. According to van Driem, “…the Opium Wars are an outcome of the British wanting to have tea but being unable to pay for this cherished commodity without resorting to the peddling of narcotics on the grandest scale ever seen in history.”

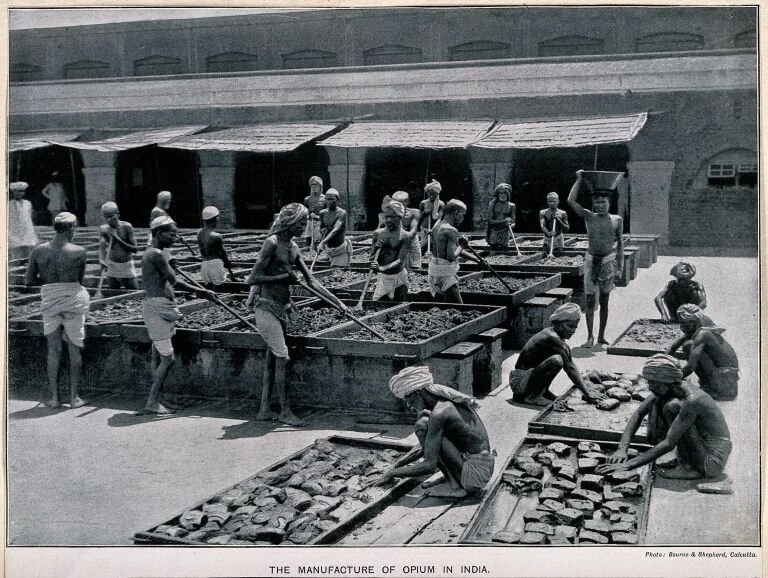

Opium production in Calcutta, India 1902. Workers mixing and balling opium for export which was an essential component of the British controlled tea trade. Photo courtesy Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons.

China sold tea and porcelain to Britain which Britain paid for with silver. In order to have enough silver to buy tea, Britain via the East India Company sold opium grown in India to make up for their trade deficit. Selling highly addictive opium was illegal in China, however. In 1839 when a Chinese official confiscated a cache of 1,200 tons of British smuggled opium into China, he ordered it destroyed. The British took that as a pretext to attack and declare war starting the first Opium War. Winning the Opium War gave British traders access to more trading ports and privileges for their citizens living in China.

Canton Waterfront, 1840. Depiction of the European trading outposts in the Chinese port of Canton, an important tea-trading site in present-day Guangdong province. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

After subterfuge and state-sponsored espionage, such as smuggling tea bushes out of China, Europeans, mostly British, were finally able to create tea production in regions under their control in the early 19th century. This was the beginning of the tea plantation system in Assam and other regions of India, then Sri Lanka, Indonesia and eventually in Kenya, Tanzania and Rwanda in the 20th century.

The loaded word of plantation accurately places these British created and controlled growing areas in the company of sugar plantations in the Caribbean and cotton plantations in the American south. Those two industries were models for the British tea growing operation.

For instance, Thomas Lipton, a name you might recognize, worked on tobacco and rice plantations in America as a teenager and those experiences informed how he set up his tea operation in Sri Lanka.

In his book Tea War: A History of Capitalism in China and India, Andrew Liu details how, “The colonial Indian industry took off only after planters employed penal labor laws to relocated indentured workers, known as ‘coolies’ from central India to Assam where they toiled on sprawling plantations described euphemistically as ‘tea gardens.’” The brutal system of kidnapping and deception to recruit labor, forcibly dislocating populations to work the tea fields as indentured labor, and employing violent methods to coerce labor resembled slavery in nearly all ways except name. And that’s only because the British wrote the laws that defined what they were doing as “not slavery.”

Tea workers in a British tea factory in Assam, Bourne and Shepherd. Photo courtesy Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons.

A large share of top tea-producing regions today simply inherited the infrastructure and means of production set up under this colonial system. While the tea industry in former British colonies like India, Sri Lanka, Kenya and Tanzania are no longer technically British, many are still reproducing value systems of colonial economics and inequalities. Instead of production serving a colonial state and an imperial industry, these old supply chains now serve key players in the global tea trade: European-based multinational corporations like Unilever or ABF.

You can be an Indian, Chinese, Kenyan or Sri Lankan tea grower, running a tea plantation which is no longer British, and still be working in a colonial system. Decolonizing does not simply mean taking over colonial systems and repopulating them with non-Europeans. The simple color of your skin and legal status of the land you are growing is not what makes something inherently colonial or not—it is a question of who is this system set up to benefit and at whose expense? Based on what value system? Who is profiting and who is being exploited? In answering those questions, we start to actually decolonize the tea production and global trade market. It is interrogating these deeper issues and examining power systems that lead to confronting the colonial mentality in tea.

***

My own childhood memories of drinking tea are themselves wrapped up in post-colonial ideas of value and worth. Growing up as a fourth-generation Chinese American in 1980s and 1990s California, my childhood was populated by tea in short ceramic cups spinning on the lazy susan on pink tablecloth covered round tables at boisterous family dim sum gatherings. A watery and bitter dark oolong tea was on offer at every potluck lunch or refreshment break in an electric dispenser at our Chinese Baptist church community. Both my parents’ families come from different southern Chinese tea-growing regions, but nobody in my family seemed particularly enthusiastic about or interested in tea. Tea was a background accompaniment, it wasn’t an occasion, focus or formal ritual in itself.

My first memory of a ceremonial tea-centered and “elevated” experience of drinking tea was when my parents took our family to a British-style afternoon high-tea at The Empress Hotel in Victoria, British Columbia. I was in elementary school. Getting dressed up as a family, to sit in the airy, elegant lobby of a luxury hotel drinking tea with a tea cup and saucer, tiered plates and ritualized finger foods was such a novel experience that it left a deep impression on me.

British-style high-tea with my mom and sister at The Empress Hotel in 1992. Photo owned by Charlene Wang de Chen.

For a long time, I considered this style of British tea drinking the pinnacle of an elegant and refined tea experience, and is what jump started my lifelong fascination with, curiosity about and love for tea. It wasn’t until recently that I had the tools and perspective to look back at this formative experience to re-contextualize just how colonial this encounter with tea was. (I was in a hotel named “The Empress” in a city named “Victoria” on Lkwungen land for starters.)

***

Her grandfather and father were already in America running a laundromat and restaurant, but my mom grew up in Hong Kong in the 1950s and ’60s before joining the rest of her family in America in the 1970s. My mom grew up as a British colonial subject in the British colony of Hong Kong. Hong Kong became a British colony as a term of the Treaty of Nanking ending the first Opium War in 1842.

Even though Cantonese Chinese is her first language and my mom grew up with a grounded Chinese cultural identity, I can see the legacy of her childhood in a British colony from her affinity to Ovaltine, Seville orange marmalade, knowledge of Princess Margaret stories from the 1960s to her admiration of British style afternoon tea.

My parents made the conscious decision to make English my first language to set me up for success in America. I grew up almost entirely educated with the Western gaze in American public schools. My education was grounded in the primacy of the Western canon and surrounded by a popular culture that maintained a reflexive understanding of white Euro-American ideas and culture being superior and the rightfully dominant force in the world. My parents tried their best to supplant this education with weekly Chinese school lessons and practices like celebrating Chinese holidays as well as cultivating a curiosity and interest in other cultures.

It has taken a long time for me to personally decolonize my own learned reflexes toward assumed Euro-American dominance and superiority. It was a process to understand that fancy-seeming European food rituals that surrounded tea were not better than the casual Chinese and Chinese-American food and tea rituals that I grew up with. Eventually I would learn about celebrated, formal, ritualized and luxurious Chinese tea traditions that have existed for centuries—and that are still enjoyed in places including Hong Kong. The historical facts of the world tea trade taught me that in fact Europeans and American themselves originally had great admiration for Chinese tea culture.

***

Chinese tea as a luxury status symbol in the 17th and 18th centuries is what created the literal thirst to reshape global tea trade for European colonists. Only aristocrats and the wealthiest could afford tea as a coveted display of elite social position and education. In Europe and the U.S. at that time, tea was what a limited-edition sneaker drop or Perigord black truffles is today.

Considering how much Europeans and colonial Americans looked to Chinese and other Asian tea traditions as the inspiration for European and American tea cultures, why were my friends so eager to bring French tea into Asian tea producing countries? How can a repackaged product assume the mantle of superiority even when surrounded by a whole culture and ecosystem of fresher and higher quality products?

The social and psychological aspect of colonialism and the cultural attitudes created to prop up the commercial side of colonialism strategically created this dissonance. In her book Thirst for Empire: How to Shaped the Modern World, Erika Rappaport shows how the British created a domestic market for the teas they were growing in their colonial empire to lure consumers away from the Chinese tea they were used to drinking through a systematic campaign of racism and fabricating a fear of the “dirty” foreign other.

One example she cites to reflect the 19th century belief that British industrial methods were inherently superior to the traditional Chinese methods for making tea were illuminated in the popular book “The Tea Controversy: Indian versus Chinese Teas. Which are Adulterated? Which are Better?” written by Edward Money in 1884.

“Indian tea was grown and manufactured on large estates under the superintendence of educated Englishmen. In China, however, tea was produced near the cottages of the poorer classes, collected and manufactured in the rudest way with no skilled supervision. Tea of Hindustan is now all manufactured by machinery, but in China it is hand-made. The latter is not a clean process…It is a very dirty process.”

In 1895, The Indian Tea Association (a British Colonial body) sent advertisement copy to American magazines with the caption: “Ceylon and Indian tea is prepared entirely by machinery, which eliminates all chance of contamination from nude, perspiring, yellow men, and preserves its natural aroma, flavor, and purity.”

Tea leaves are hand rolled to produce the shape for a distinctive regional tea in Anhui, China. Photo by Charlene Wang de Chen, Tranquil Tuesdays.

These sentiments of racial superiority and inferiority coupled with fear of “foreign dirtiness” still seem to echo in our culture. In the words of Rappaport, “We can see that tea was arguably one of the slowest industries to shed the racial, class, gender, and labor hierarchies born in the colonial era.”

Our 21st century admiration of handcrafted artisanal food products in the face of large-scale industrialized food has not completely erased these racist ideas from the 19th century. Handcrafted Italian cheeses somehow still occupy a strata of the gourmet food hierarchy that handcrafted Chinese teas do not.

Today, teas are often compared to wines and wine culture in order to gain legitimacy as a gourmet product worthy of attention and esteem. Why does tea need to be compared to a European drink tradition in order to be taken seriously? Tea has been taken seriously for centuries by many cultures for whom European wine cultures mean very little.

How come so many consumers are specifically seduced with branding such as Mariage Frères or the many heritage British tea brands that play up the romanticism of colonial tea trading? Why is that colonial heritage considered a plus and not a detriment? Through the internet, we have direct access to artisanal growers and crafted whole-leaf single-origin teas. Colonial tea trading brands seem like they should be irrelevant by now.

One of the colonial legacies of the tea trade is the commodification of tea where the value of the tea leaf itself has become obscured. Instead the value seems to be imbued in the packaging and branding of the trader and not in the value of the grower or the people who craft and finish the teas.

***

By the time I had my first job working as a diplomat for the U.S., I had become the kind of tea-oriented person who had a steeping cup in the office and a selection of loose leaf tea blends in my desk drawer.

When I was brought along to a meeting of senior diplomats while working at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, I was busy taking notes when a cup of loose-leaf-brewed tea was handed to me by our Chinese hosts.

Today I cannot recall who was at that meeting, what the topic of that meeting was, or what was discussed. But 12 years later I can tell you with clarity the moment I first took a sip of that tea and how all my senses rose to attention and changed everything I thought I knew about tea. The flavor was soft, round, there was a fresh greenness, and then it ended in a taste that was velvety almost creamy. The crisp, light-yet-clear notes of the flavor conveyed a freshness I had never experienced with tea before. I peeked into the cup and saw a bunch of little flat green tea buds floating freely in the cup of water. All I could think was Tea can taste like this? What was everything I was drinking before?

The answer to that was everything I was used to drinking before was the kind of tea colonial trading histories made widely available to drinkers in North America and Europe: a shelf stable commodity made from lower grade summer harvests, cut up pieces of leaves and dust from an industrial manufacturing process called CTC (cut-tear-curl), a blend of dried leaves from multiple growing regions. Often, this tea would have spent a while in warehouses and on shelves before ending in my cup. As a result of all this, tea that I was used to drinking was often lackluster and flat or dominated by flavoring agents or “special blends” to create more pizazz.

I didn’t realize that if you drank whole leaf teas fresh enough there was a whole symphony of flavors in the pure leaves themselves they did not require any additional scents or blended elements to be a whole taste experience. European tea brands like Mariage Frères specialize in scented blended teas. Because of unchecked assumptions, inherited colonial mentalities, and weakness for fancy packaging, we often believe that whatever European luxury brands were doing must automatically be the height of refinement and gourmet savoir faire. Instead of being the pinnacle of great teas, flavored and blended teas were a merchant’s trick to mask lower quality and cheaper teas in order to mark them up. Creating special tea blends is a colonial branding trick to distract the tea experience away from the grower and pretend the value lay in the hands of the seller.

The journey from luxury single-origin whole leaf teas toward a blended and branded often cut-up and torn mass consumer good has everything to do with the large scale industrialization to benefit the colonial enterprise. With Britain in the 19th century controlling the large-scale plantations producing tea in India and Sri Lanka, it became an industrial product. Like many other foods and agricultural products that have undergone industrialization in our food supply, tea became just another product that big businesses wanted to flatten into a uniform commodity that was interchangeable and indistinguishable in its sameness, something that could taste the same everywhere and not be from anywhere in particular until it was branded by the seller.

The practice of blending and branding in teas also transformed the supply chain. Now traders were trying to make diverse teas from multiple origins conform to colonial trading categories of classification created for the benefit of commerce, instead of looking for taste or quality. Industrialization and colonial trading bred consumer ignorance and disconnection with the fact tea is an expression of a living plant. It is fascinating to note that even British tea planters stationed in India during the 19th century colonial era objected to blending teas because they knew this practice erased the drinker’s and consumer’s knowledge of and relationship to the tea’s growing origin.

Tea picking in Phoenix Mountain, Guangdong one of China’s famed tea terroirs. Photo by Charlene Wang de Chen, Tranquil Tuesdays.

Restoring the relationship between the tea leaves in your cup and a single origin allows your taste buds to reconnect with the flavors of terroir. It is also probably the easiest first step you can take in your efforts to decolonize tea. As you start to build a taste relationship with the tea plant, you can begin to appreciate the impact of the producer’s cultivation, harvesting, shaping, drying and curing skills. This newly heightened taste awareness of tea helps challenge assumptions of what makes a tea worthy and of value. Lastly, the ultimate way we can decolonize tea is to redistribute the wealth in the tea industry away from brands, traders and middlemen and back to the source of the tea.

Freshly picked tea leaves in Wuyuan, Jiangxi, one of China’s historically export-oriented tea terroirs. Photo by Charlene Wang de Chen, Tranquil Tuesdays.